MIGNEX Insight

Forced migrant returns risks undermining EU’s development aid strategy

A team of MIGNEX researchers has spoken to more than 13,000 young adults across 26 communities in Africa, Asia and the Middle East about the impact of forced returns on local development.

A version of this article was originally published by EUObserver (euobserver.com)

The EU’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum, approved last week by the European Parliament, provides for many more migrants to be forcibly returned to their home countries.

NGOs including Amnesty International have said the deal will put migrants at increased risk of human rights violations, whereas broadly centrist governing parties will be relieved to be able to go to voters at this year’s European elections with an answer to their concerns about migration.

What hasn’t been much discussed is the likely impact of more forced returns on migrants’ home communities – and it’s not good news.

I am part of a team of researchers that has spoken to more than 13,000 young adults across 26 communities in Africa, Asia and the Middle East about the impact of migration on local development.

We found that forced returns can have a range of harmful effects on migrants’ home communities, whereas return migration was connected to better well-being when it was not forced. In more than half of the communities, we saw lower poverty and higher wealth levels when returns were not in the form of deportations.

Why forced returns has negative consequences for development

The discrepancy may be a result of forced returnees being traumatised by their experiences and needing care by the community rather than contributing to it. Across our whole research sample, 15 percent of people knew somebody who had been detained during a migration, or had themselves been detained. Twelve percent knew somebody who had been injured, or had been themselves, and 13 percent knew somebody who had died.

In some communities these numbers were starkly higher. In Behsud, a town in central Afghanistan that is home to large numbers of the persecuted Hazara community, more than half of people we spoke to knew somebody who had died on their way to another country.

More simply, home communities may lack economic opportunities for deportees, particularly if they haven’t spent enough time in Europe to acquire capital or new skills. In these cases, the returnees may have no opportunity to meaningfully reintegrate into society. This can lead to an increase in unemployment and criminality.

“Returnees become a burden to the town,” said a woman in Kombolcha, a town in northern Ethiopia on the frontlines of the recent Tigray War. “They are taking jobs that might otherwise be available to non-migrants.”

The picture is clouded by a number of benefits to home communities associated with voluntary return migration. For example, there are generally positive effects on living standards in communities of origin. Such returnees might have acquired the necessary capital or social connections to start a business, or simply picked up valuable new skills while working in Europe.

A man in Golf City, a development outside the Ghanaian capital Accra, told us that people returning in this way can have many positive effects on the community, for example by creating employment: “When we consider e-commerce for instance, when one travels and gets to acquire some knowledge and expertise in this field, he can return and establish his own business and then employ a lot of the youth who do not have anything to do.”

Development aid as a bargaining chip for returns

EU policymakers are keen to play up this positive aspect of migrant returns. A new EU development instrument, known as NDICI-Global Europe, contains a 10 percent “migration component” under which actions for border and return management can be financed. Developing countries that cooperate with the EU on readmitting their nationals or on border management can be rewarded with additional funding.

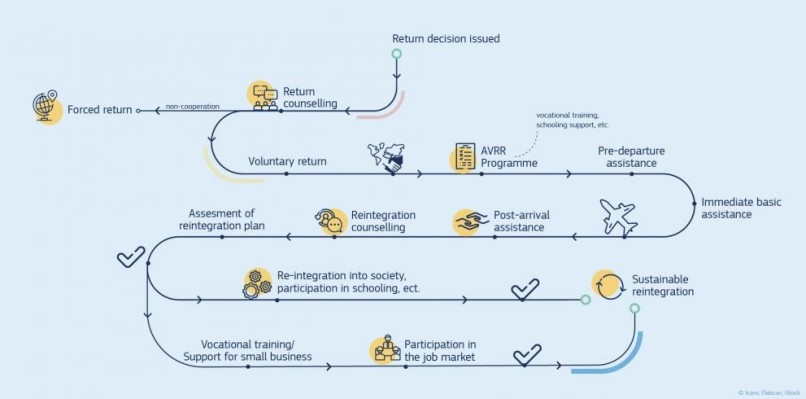

There are restrictions on directly classifying forced returns as development aid. The OECD said last year that the funding of forced returns was not eligible to be reported as “official development assistance” (ODA). And the European Commission’s own returns policy gives “preference to voluntary return”.

But those restrictions require a clear definition of a forced return, which is lacking in the EU’s strategy. In the Commission’s policy, a return is only classified as forced if a migrant actively resists deportation. A migrant who cooperates with a “return decision”, thereby accessing various bits of assistance, is said to be a “voluntary return”.

Clearly this scenario, which involves a heavy dose of coercion, is very different from a migrant prospering in Europe for a few years and then freely deciding to return home, which is the situation most likely to provide a good development outcome.

Clearer definitions and safeguards are needed if the EU is to develop an evidence-based development aspect to its returns policy. A single-minded focus on return, without adequate consideration of other aspects of migration and development, will lead to incoherent policies with adverse consequences.

Under the EU’s new migration pact, a greater number of forced returns is inevitable. Policymakers should be honest about the effect this will have not only on migrants but also their home communities, and recognise that it may exacerbate the conditions that cause people to migrate in the first instance.

Zina Weisner is a PhD researcher at the Department for Migration and Globalisation of Danube University Krems in Austria. As part of the MIGNEX (Aligning Migration Management and the Migration-Development Nexus) Project, her research focuses on the causes and consequences of migration as well as the role of development and humanitarian aid in the external dimension of EU migration governance.